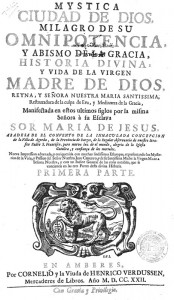

- Opening page of a vita of Sta. María de Jesús de Agreda (1602-1665), Spanish Fransiscan.

- Portrait of María de Jesús de Agreda (1602-1665)

Maria Coronel y Arena (1602-65) born in the village of Ágreda in northern Spain on April 2, 1602. She was the third child of Don Francisco Coronel and Catherine d’Arena.[1] Motivated by a divine revelation, her parents founded a convent in their own house on January 19, 1619.[2] Mary assumed the nun’s habit along with her mother and sister on February 2, 1620.[3] At the age of twenty-five, Mary was elected mother superior of the convent with papal approval, and managed the convent until her death in 1665.[4]

Mary of Ágreda is mainly known for three components of her life: her mystical experiences and bilocation to the New World, the correspondence she maintained with King Philip IV for twenty-two years, and her written work on the life of Virgin Mary, titled the Mystical City of God.[5]

In April 1631, Fray Alonso de Benavides, former custodian of conversions in present day New Mexico, visited Mary in Ágreda accompanied by two other Franciscan friars, Father Francisco Andres de la Torre and Father Sebastian Marcilla. The purpose of this visit was to interrogate Mary about her involvement in the evangelization of indigenous peoples in the New World.[6] It is said that a decade earlier, she reveled to her confessor a series of mystical trances in which she traveled to the region of present day New Mexico. Fray Alonso and the two Franciscan friars were to investigate Mary of Ágreda in 1631 after Alonso de Benavides published a text titled Memorial, where he mentioned Ágreda’s miraculous conversions in New Mexico.[7] Apart from this interview, the Holy Office of the Inquisition investigated Mary of Ágreda on multiple occasions. Different authorities of the Holy Office analyzed her writings and her confessors, fellow nuns and acquaintances were interviewed during her lifetime and after her death/ but she was never charged or tried by the Inquisition.[8]

During interrogation, a delegation of Jumano Indians stated that a mysterious lady in blue “had instructed them the rudiments of the Christian faith and urged them to seek the friars for baptism.”[9] Thus, regardless of whether the mysterious lady in blue was in fact Mary of Ágreda, it is important that the story of her bilocation has permeated the historical accounts and myths of different peoples in Southwest America and Latin America. Likewise, her name has remained alive as an important one in the spiritual conquest of the New World.[10]

Most of the information about her bilocation comes from “the texts and testimonials of others, usually men, who disseminated this story with specific, indeed imperialist goals in mind.”[11] The personal interests of individual frays were involved in the diffusion of her mystical experiences because, at that time, there were conflicts between the different evangelizing orders in the New World.[12]

Mary of Ágreda only mentions her bilocation in two documents written almost twenty years apart. The first one was written in 1631, after her interview with fray Alonso de Benavides. He requested Mary to write a letter directed to the Franciscan missionaries working in New Mexico to encourage them in their task of converting locals.[13] She opens this letter by clarifying that she is writing in obedience to her religious superiors, and describes her visits to Indian communities in the New World. Finally, she describes the resistance to conversion of some members of Indian communities which feared Christianity as a source of evil.[14] Her letter was attached to a letter written by Fray Benavides, who explains that the nun was “transported by the aid of angels that she [had] as guardians”.[15] These letters were published again in Mexico in 1730 and 1743.[16]

Later, in 1650, Mary of Ágreda mentions her spiritual journeys to the New World in a letter she wrote to Pedro Manero of the Inquisition. In this letter, Mary attempts to clarify some of the information included in Benavides’ Memorial published in 1631, arguing that some of the details included were not false, but had been exaggerated. In this document, she does not deny the events of her bilocation, but provides her own account.[17] She “always maintained that she was unsure as to whether she traveled to the New World in corporeal form or only in spirit, or whether it may have been an angel disguised at her.”[18]

By the time Mary of Ágreda wrote this document, she had already established a close relationship with King Philip IV, with whom she began corresponding after they met. The King had heard of the saintly abbess, and decided to visit her on his way to Catalonia in 1643. Her “words, manner and appearance were enough for the king to insist upon exchanging regular correspondence with her after the one short visit he made to Ágreda.”[19] They exchanged more than 600 letters in which Mary advised the King on spiritual and political grounds until her death.[20]

Apart from the stories of her bilocation and her relationship with the King, Mary is well known for her controversial account of the life of Virgin Mary. For ten years, Mary of Ágreda was commanded by God and the Virgin Mary to write the life of the virgin, but that she refused this call until 1637. [21] Yet, once she completed the work, she destroyed it along with other compositions on other subjects. Her superiors and first confessors reprimanded Maria for destroying her work, and commanded her ti write the life of Mary again.[22] On December 8, 1655, Mary of Ágreda began to write the life of Virgin Mary one more time. Upon completion, this work was titled The Mystical City of God , consisting of three parts which were compiled in eight separate books. The work was later printed in Lisbon, Madrid, Perpignan, and Antewerp. The Spanish edition was translated into French in Perpignan by Father Croset and printed in Marseille in 1696.[23]

Mary of Ágreda claimed that the Virgin herself had dictated the account of her life. This multivolume text generated great controversy in Paris, where some members of the theological faculty at the Sorbonne demanded its censure, while others opposed such a demand. This censure was argued mainly on the grounds of Ágreda’s defense of the Virgin’s immaculate conception.[24] Later, in 1681, The Mystical City of God was included on the Index of Forbidden Books by the Inquisition. Nevertheless, Mary of Ágreda was never condemned “on the grounds of ‘Blessed Innocence.”[25] After her death on May 24, 1665, there were reports of miracles attributed to her; there were efforts of behalf of King Philip IV and Spanish bishops for her beatification. Other religious authorities, like Pope Clement X praised her virtues and declared her ‘venerable.’[26]

[1] Marilyn H. Fedewa, María of Agreda: Mystical Lady in Blue (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2009), 12.

[2] Mary Hays, “Mary de Agreda,” Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries (6 volumes) (London: R. Phillips, 1803), vol. 1, 6-10, on 6.

[3] Hays, “Mary of Agreda,” vol. 1, 6-10, on 6.

[4] Carme Font, “Mary de Agreda,” Mary Hays, Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries (1803). Chawton House Library Series: Women’s Memoirs, ed. Gina Luria Walker, Memoirs of Women Writers Part II (Pickering & Chatto: London, 2013), vol. 5, 32-6, editorial notes, 414-15, on 415.

[5] Katie MacLean, “María de Agreda, Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” Colonial Latin American Review, 17, No.1, (June 2008): 30. Accessed June 18, 2014. DOI: 10.1080/10609160802025409

[6] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 29.

[7] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 32.

[8] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 32.

[9] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 30.

[10] Fadewa, “Mystical Lady in Blue,” xiii.

[11] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 41.

[12] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 37–41.

[13] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 33.

[14] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 33-4.

[15] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 33.

[16] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 43.

[17] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 33.

[18] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 30.

[19] MacLean, “Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest,” 30.

[20] Marilyn H. Fedewa, Sor Maria de Jesus de Agreda: Life & Works of the Lady in Blue, Cambridge Connections : Accessed June 19, 2014, http://www.cambridgeconnections.net/Maria_Life.html.

[21]Hays, “Mary de Agreda,” vol. 1, 6-10, on 7.

[22] Hays, “Mary de Agreda,” vol. 1, 6-10, on 7.

[23] Hays, “Mary de Agreda,” vol. 1, 6-10, on 7.

[24] Font, “Mary de Agreda,” vol. 5, 32-6, editorial notes, 414-15, on 414-15.

[25] Font, “Mary de Agreda,” vol. 5, 32-6, editorial notes, 414-15, on 415.

[26] Font, “Mary de Agreda,” vol. 5, 32-6, editorial notes, 414-15, on 415.

Bibliography:

Fedewa, Marilyn H. María of Agreda: Mystical Lady in Blue. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2009.

Font, Carme. “Mary de Agreda.” Mary Hays, Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries, 1803. Chawton House Library Series: Women’s Memoirs, ed. Gina Luria Walker, Memoirs of Women Writers Part II. Pickering & Chatto: London, 2013, vol. 5, 32-6, editorial notes, 414-15.

Hays, Mary. “Mary de Agreda.” Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women of all Ages and Countries (6 volumes). London: R. Phillips, 1803, vol. 1, 6-10.

MacLean, Katie. “María de Agreda, Spanish Mysticism and the Work of the Spiritual Conquest.” Colonial Latin American Review 17, No.1 (June 2008): 29–48. Accessed June 18, 2014.

MacLean, Katie. Review of María of Agreda: The Mystical Lady in Blue, by Marilyn Fedewa. The Catholic Historical Review, 100, No.2, Spring 2014.

Rissie, Katherine. “Revising a Matrimonial Life: An Alternative to the Conduct Book in María de Agreda’s “Mística ciudad de Dios“, MLN 123, No. 2 Hispanic Issue, (March 2008): 230–251. Accessed June 18, 2014.

Vollendorf, Lisa. The Lives Of Women: A New History of Inquisitional Spain. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2005.

Page citation:

Juliana Ossa Martinez. “Mary of Ágreda.” Project Continua (April 7, 2015): Ver. 1, (date accessed), http://www.projectcontinua.org/mary-of-agreda/

Tags: Abbesses, End of Renaissance, Europe, Reformation, Writers