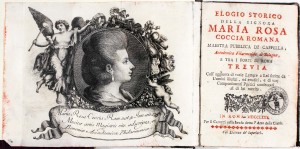

- Muller Collection, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Maria Rosa Coccia

by Marie Caruso

Italian composer and teacher, Maria Rosa Coccia (1759-1833) was the first woman to achieve the qualification of Maestra di Capella (Chapel Master) of Rome. What historians have most often remembered about her were not her accomplishments, but the controversy that developed over the publication of her extemporaneous entrance exam for the Accademia di S Cecilia. This controversy was a result of the claim made by Francesco Capalti, Maestro di Cappella of the Cathedral of Narni, that Coccia’s exam contained errors and that she was only promoted because she was a woman. A biographical booklet entitled Elogio Storico della Signora Maria Rosa Coccia Romana […],[1] was compiled in her defense in 1780 by Abbate Michele Mallio.

Coccia, a child prodigy, dedicated her first composition, six Sonate per cembalo, to Prince Charles Edward Stuart, when she was 12 years old.[2] A year later Coccia composed an oratorio,Daniello nel lago dei leoni, dedicated to the Duchess Marianna Caetani Sforza-Cesarini. This was an extraordinary endeavor for a young girl in eighteenth-century Rome, a Papal state, where women were prohibited from attending a performance of an oratorio, let alone composing one (Johnson 1987:5).[3] Coccia was dependent on patrons for their cultural connections and financial support. She was never able to attain steady patronage and worked as a freelance artist. Throughout her career, Coccia demonstrated a strategy of targeting mostly wealthy, powerful women who might be sympathetic to her.

Granted admission into the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna in 1779, Coccia continued to compose both secular and sacred music until 1783. The last fifty years of her life remain an enigma. It is not known if her music was lost or if she stopped composing. A collection of minuets by Coccia, dated 1783, was recently discovered in a Neapolitan convent. Although this does not solve the mystery of the sudden end of her music, it does augment her life’s narrative.[4]

The last evidence we have of her whereabouts is a plea for a monthly stipend written in 1832, one year before her death, to the Accademia di S Cecilia. In this last letter, Coccia stated that she had been a composer and teacher all her life, but because she was responsible for the care of two ailing parents and a sick sister, she did not have even a small savings for her old age. Her ill health prevented her from teaching. She was granted a small pension and died on November 21, 1833.[5]

1 Mallio, Michele. 1780. ElogioStorico Della Signora Maria Rosa Coccia RomanaMaestraPubblica Di Cappella, AccademicaFilarmonica di Bologna, e tra I Forti di Roma, Trevia, Coll’Aggiunta di varieLettere and Lei scritte da Uominiillustri, ederuditi, e di variComponimentiPoeticiconsecrati al di lei merito, Roma: Cannetti

2 Conserved in the St. Cecilia library in Rome (ms. A. 194) and dated March 14, 1772.Can be viewed online: http://bibliomediateca.santacecilia.it

3 Johnson, J., “The Papacy looked with such disfavor upon women performing that they were prohibited from singing in Roman theaters until 1798. Nor could women perform in, or even attend, oratorios” (5).

4 Two minuets from this collection, Minuet V for harpsichord and violins, and Minuet XV for harpsichord, were recorded by William Buthod, Music Director of St Mary’s in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

5 Cametti, op. cit., 343-344.

Vingt Menuets Pour le Clavecin à l’usage de Son Exellence M: Henriette Milano composès par Marie Rose Coccia Maitresse de Chappelle ed membre de l’Academie Philarmonique de Bologne À Rome, le 20 d’Avril 1783, Archivio di Monastero Benedictino in Naples, San Gregorio Armeno, N. 657 – William Buthod

Tags: Composers, Enlightenment, Europe, Industrial Revolution, Musicians