Mary Hays (1759-1843) was a novelist, best known for her belief in radical feminism as an expression of enlightened Dissent, and her provocative history of women. She was born in 1759, into a family of Protestants who rejected the practices of the Church of England.[1] Hays was described as ‘the baldest disciple of [Mary] Wollstonecraft’, attacked as an ‘unsex’d female’, and provoked controversy through her long life with her rebellious writings.[2] When Hays’s young lover died on the eve of their marriage, Hays expected to die of grief herself, but realized that she could now escape an ordinary future as wife and mother.[3] She seized the chance to make a career for herself in the larger world as a writer.[4]

Hays read Mary Wollstonecraft’s fiery A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792.[5] She acted on Wollstonecraft’s demand that women take charge of their lives and moved out of her mother’s home to live as an independent woman in London. This was an extraordinary and unaccustomed act for a single woman in Hays’s time: Hays’s mother was horrified, and Hays’s friends condemned her.[6] Although Hays’s family were outsiders from mainstream British culture, Hays’s mother still disapproved of her daughter’s social rebellion. Women did not live independently at the time; even the nonconformists to British society, such as those in Hays’s own family, adhered to conventional gender norms. Hays experimented with ‘the idea of being free’, earning her own living and actively pursuing the man she loved, a handsome Cambridge University mathematician, William Frend.[7] Hays turned the tables on conventional courtship by declaring her passion to him. However, while he supported her career, Frend rejected Hays’s romantic feelings towards him. Hays used her romantic heartbreak as the subject of her bestselling novel, Memoirs of Emma Courtney, published in 1796. Readers were shocked because Hays included real letters she had exchanged with William Godwin, leading radical philosopher, and Frend. Emma, Hays’s ‘fictional’ heroine, tells the Frend figure that her desire for him trumps every other consideration: reputation, status, and even chastity. In the most notorious statement in the book, Emma plays on Frend’s name: ‘My friend’, she cries, ‘I would give myself to you – the gift is not worthless’. In real life and in the novel Frend rejected Hays. Hays’s disgrace was juicy gossip in the close-knit group of London publishing.[8] Then Scottish writer Elizabeth Hamilton published Memoirs of Modern Philosophers (1800), a novel that satirized Hays as a sex hungry man-chaser, and Hays became a laughingstock throughout Britain.[9]

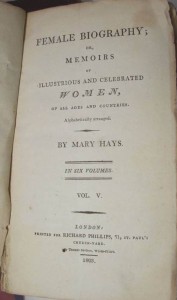

At the lowest point in her life, living alone, rejected by the man she loved, and an object of derision, Hays turned to a new project which she called Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries, published in 1803 in six volumes. Hays included women of every kind of moral character, including rebellious women like her. Female Biography broke new ground: previous collective biographies of women included only pious ladies who were meant to serve as examples to their female readers. In Female Biography she imagined a community in which women of all historical eras, nationalities, political and religious beliefs, reputation, and classes, invited the reader into their world. Female Biography attracted global attention; reviewers in Britain, France, and the United States criticized Hays’s decision to include immoral women, but despite the negative attention, the books sold well and generated enough royalties for Hays to buy a ‘cabin’ of her own outside London. Jane Austen’s aristocratic sister-in-law, Lady Elizabeth Austen Knight, was given Female Biography as an anniversary present by her oldest son in 1807. It is likely that Jane Austen consulted Hays’s work in the Austen Knight library at Godmersham, their estate in Hampshire, when she paid long visits.[10] Jane Austen revised existing manuscripts and composed new novels in the Godmersham library.[11] Hays’s ‘female biographies’ may have even encouraged Austen to create intelligent, adventurous heroines of her own.[12] The Chawton House Library Edition of Female Biography (Pickering & Chatto, 2013, 2014), edited by Gina Luria Walker, complements Hays’s original with new annotations by 164 international scholars.[13]

After her older sister died suddenly, Hays raised her young nieces and ran a private girls’ school which they attended. She responded to the changing times during the sensational ‘Queen’s Trial’ in which King George IV tried to divorce his wife, Caroline of Brunswick, on grounds of adultery. ‘The Caroline Affair of 1820’ galvanized public opinion, uniting the social classes in defending the honor of the queen. Caroline appealed successfully to the people who supported her against the unpopular king. The divorce was not granted.[14] In Memoirs of Queens (1821) Hays assembled individual women’s stories to document her belief that historically queenship offered the only unobstructed sphere in which female power could be fully exercised.[15] In her memoirs of Elizabeth, Catherine II, Catherine de Medici (Queen of France), and other dominant monarchs, Hays argued that female succession and rule demonstrated that queens could rule as well or even better than their male counterparts. Hays predicted that with the increasing participation of women in public life, ‘all things will become new’.[16]

No image survives of Mary Hays who considered herself without physical attractions.[17] She was mocked by some of her contemporaries for her alleged homeliness.[18]

[1]Gina Luria Walker, Mary Hays 1759-1843: The Growth of A Woman’s Mind (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2006), 75–6.

[2] The English Review, 22: 253-7, 1793, quoted in Walker, Mary Hays, 75-6; and Reverend Richard Polwhele, The UnSex’d Females: A Poem (Cadell and Davies, 1798).

[3]Walker, The Growth of A Woman’s Mind, 61-4.

[4] Walker, The Growth of A Woman’s Mind, 61-4.

[5] Walker, The Growth of A Woman’s Mind, 61-4.

[6]Walker,Growth of A Woman’s Mind, 121-3.

[7] Walker, The Growth of A Woman’s Mind, 121-3.

[8]Walker,Growth of A Woman’s Mind, 173-6.

[9] Walker, The Growth of A Woman’s Mind, 173-6.

[10]“Introduction,” Mary Hays, Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries (1803) Chawton House Library Series: Women’s Memoirs, ed. Gina Luria Walker, Memoirs of Women Writers Part II (Pickering & Chatto: London, 2013), vol. 5, xiv.

[11] Gina Luria Walker, Chawton House Fellow’s Lecture, “Pride, Prejudice, Patriarchy: Jane Austen Reads Mary Hays,” (University of Southampton English News, Jane Austen Society of North America, 2010).

[12]Walker, “Pride, Prejudice, Patriarchy: Jane Austen Reads Mary Hays.”

[13] Walker, “Pride, Prejudice, Patriarchy: Jane Austen Reads Mary Hays.”

[15]Walker, “All Things Will Become New,” Growth of A Woman’s Mind, 229-34.

[17]Walker,Growth of A Woman’s Mind, 87 and passim.

Works Consulted:

Clemit, Pamela ed. Letters of William Godwin, Volume 1: 1778-1797. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Clemit, Pamela and Gina Luria Walker eds Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman(1798) by William Godwin. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2001.

Godwin, William, and Mary Hays. Mary Hays Correspondence and Manuscripts. The Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Hays, Mary. Cursory Remark on an Enquiry into the Expediency and Propriety of Public or Social Worship: Inscribed to Gilbert Wakefield, B.A….by Eusebia. London: T. Knott, 1792.

Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women of All Ages and Countries. London: Phillips, 1803.

Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries (1803). Chawton House Library Series: Women’s Memoirs, ed. Gina Luria Walker, Memoirs of Women Writers Part II (Pickering & Chatto: London, 2013, 2014).

Letters and Essays, Moral, and Miscellaneous. London: T. Knott, 1793. Reprinted 1974, Garland Publishing, with new introduction by Gina Luria.

“Memoirs of Mary Wollstonecraft” The Annual Necrology for 1797-8. London: Phillips, 1800.

“Obituary of Mary Wollstonecraft” The Monthly Magazine 4 (1797): 233.

[Polwhele, Richard]. The Unsex’d Females: A Poem: Addressed to the Author of The Pursuits of Literature. ed. G. Luria. New York: Garland Publishing, 1974.

Spongberg, Mary. “Mary Hays and Mary Wollstonecraft and the Evolution of Dissenting Feminism” in Intellectual Exchanges: Women and Rational Dissent, Special Issue of Enlightenment and Dissent 26 (2010): 230-258.

“Remembering Wollstonecraft: Feminine Friendship, Female Subjectivity and the ‘invention’ of the Feminist Heroine.” Amy Culley and Daniel Cook eds Women’s Life Writing: Gender, Genre and Authorship 1700-1850.London: Palgrave, 2012.

“Thinking the Woman: Historicising Women in the Age of Enlightenment.” To appear in eds Ned Curthoys, Shino Konishi and Alex Cook. Representing Humanity in the Age of Enlightenment. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2013.

The Correspondence (1779-1843) of Mary Hays, British Novelist, edited by Marilyn L. Brooks. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2004.

Walker, Gina Luria. “‘Can Man Be Free/And Woman Be A Slave?’ Teaching Eighteenth- and Nineteenth Century Women Writers in Intersecting Communities” in Teaching British Women Writers 1750–1900. eds Jeanne Moskal and Shannon Wooden. New York: Peter Lang, 2005. (190-204)

The Idea of Being Free: A Mary Hays Reader, ed. Gina Luria Walker. Peterborough: Broadview Editions, 2006.

“Pride, Prejudice, Patriarchy: Jane Austen Reads Mary Hays.” Chawton House Fellow’s Lecture (February 2010); On line Podcast University of Southampton English News at: http://www.soton.ac.uk/english/news/news.shtml

“‘Energetic sympathies of truth and feeling’: Mary Hays and Rational Dissent.” Intellectual Exchanges: Women and Rational Dissent, Special Issue, Enlightenment and Dissent 26(2010): 259-285.

“Mary Hays (1759-1843): An Enlightened Quest” in Women, Gender and Enlightenment. eds Sarah Knott and Barbara Taylor. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. (493-518)

“Mary Hays’s Letters and Manuscripts” Signs 3.2 (1977): 524-530.

“Mary Hays’s ‘Love Letters’” Keats-Shelley Journal 51 (2002): 80-101.

“‘Sewing in the Next World’: Mary Hays as Dissenting Autodidact in the 1780s.” Romanticism On the Net 25 (2002): 45 pars. On line at http://www.erudit.org/revue/ron/2002/v/n25/006013ar.html

Mary Hays (1759-1843): The Growth of A Woman’s Mind. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006.

“The Two Marys: Hays Writes Wollstonecraft,”

“Women’s Voices” in Cambridge Companion to British Writing of the French Revolution, 1789-1800. ed. Pamela Clemit. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011. (265-294)

Wardle, Ralph M. ed Godwin and Mary: Letters of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1977.

Waters, Mary A. British Women Writers and the Profession of Literary Criticism, 1789-1832. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Wedd, Annie F. ed. The Fate of the Fenwicks. London: Methuen, 1927.

ed. The Love Letters of Mary Hays (1779-1780). London: Methuen, 1925.

Resources:

Brooklyn Museum

Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: The Dinner Party: Heritage Floor: Mary Hays

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/heritage_floor/mary_hays.php

Page citation:

Gina Luria Walker. “Mary Hays.” Project Continua (February 19, 2014): Ver. 1, [date accessed], http://www.projectcontinua.org/mary-hays/

Tags: Biographers, Enlightenment, Essayists, Europe, Industrial Revolution, Novelists